5 My Family

5.1 Sprague Family History

Upwey is a small town in the south of England, a few miles from the coast. Sometime in October of 1609, our ancestor William was born the youngest son in a family that thought the Church of England didn’t go far enough in its separation from the Roman Catholics. Upwey was hundreds of miles from the real center of people who believed like they did, a group we now call Puritans. William was only six when his father died, and with few prospects of making a living under the religious persecution that his family saw coming, in 1629 he joined his brothers Ralph and Richard on a ship called The Lion’s Whelp, for the two-month journey across the Atlantic. Soon after their arrival in Salem Massachusetts, the governor asked the Sprague boys to explore the area between two nearby rivers. After quickly making peace with the local Indians, they formed a new settlement called Charlestown, in what is now the oldest neighborhood in Boston.

William was 26 when he married Millicent Eames, the daughter of a ship’s captain, who bore him 10 children, including Jonathan, who was born in 1648. Jonathan named his son after his grandfather William, born in 1690 when the family moved to Rhode Island. William Jr in turn had a son, Joshua (1729), who moved northward to Novia Scotia and had a son Nehemiah (1770) who had a son Thomas (1804). By then the family was living in Ohio and had a son Fellman (1849), who moved to Wisconsin and had a son named Howard (1887). Incidentally, Howard had an uncle named Lafayette, who died in 1862 at Antietam fighting against slavery.

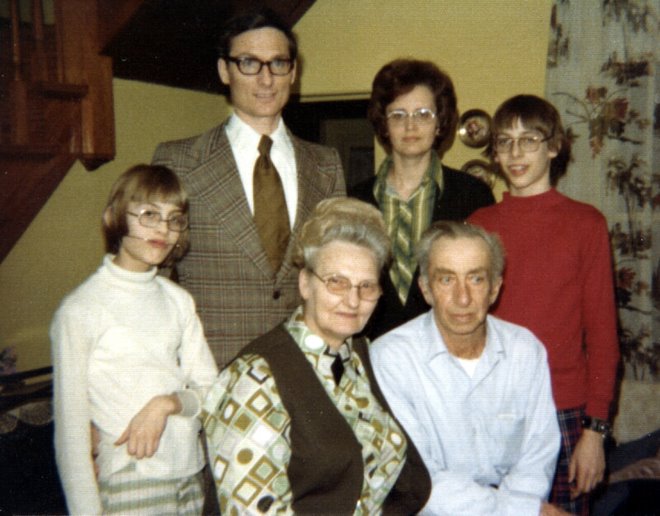

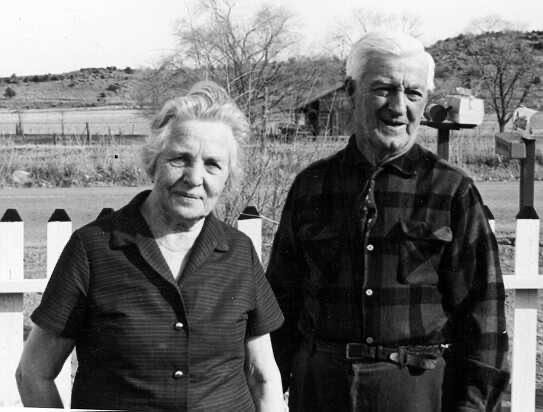

Howard lived well into the 1970s, and I was about 10 years old when I met him and his wonderful wife (and my great-grandmother) Delia. They had a son, Donald, who married Ruth Faerber, and had a son they named Donald Eugene Junior (1940) – my grandfather.

A family like ours has zillions of stories, most of which seem too mundane to bother repeating, but which somehow end up in our collective memories. Oh, not quite memories – more like feelings and intuitions, attitudes about life that seem natural to us because that’s how we were raised, but might seem unfamiliar or strange to others. Most of these are too boring to notice, like how much we slouch in a chair; some are more important, like how (or whether?) you feel guilty when you’re late or how much you trust others – and whether you think there’s a difference between lying and fibbing. We Spragues didn’t learn those things from a book or school; we got them from our parents, who got them from their parents and on and on, all the way back to William.

5.2 My Parents

Although technically the Baby Boom lasted for a few years after I was born, I never felt like a boomer. The “in-between” demographics of my family might explain why.

Both of my parents were born just before World War II, barely. When Pearl Harbor was attacked in December 1941, my mother was not yet a year old. The war was over by the time my father, born in March 1940, started school. Neither of them remembers the war, except in the inevitable first-hand stories they heard from returning veterans. My grandmother kept wartime ration coupons in an old box she would show us sometimes, like museum pieces.

If the “Baby Boom” is a mindset of children born into a time of a rapidly growing young population, then my parents belong to that generation more than I do. Although their own parents and relatives weren’t themselves returning from WWII, they directly benefited from the American optimism and economic expansion that followed.

Both grew up on dairy farms in north central Wisconsin. As teenagers in the 1950s, they were old enough that they could tease friends who had only recently installed their first telephones, indoor plumbing, or electricity. Although they never flew on an airplane themselves, they knew people who had. They can remember their first TV sets.

Donald Eugene Sprague, Jr.

My father was an only child, in a rural community in northwestern Wisconsin full of big families. He had many aunts and uncles who bred dozens of cousins, many of them living close enough to play with regularly. Despite that, he remembered his childhood as a lonely time, of a constant struggle to overcome his natural shyness.

The first of his family to attend college, he entered the nearby Eau Claire state college, intending to collect enough units to transfer to the University of Wisconsin at Madison, majoring in engineering. It was at a basketball game during the fall of his sophomore year that he met my mother for the first time.

The two of them saw each other throughout the school year until he left for Madison in the Fall of 1960. But the much bigger campus was a lonely place, and he missed my mother. When he found the engineering classes more challenging than he expected, he dropped out, working part time in a photography studio until the end of the semester.

By winter (early 1961), he was back at his hometown of Sheldon, continuing to see Patsy Pulokas until they were married in July 1961. “After I was married, I never got less than an A in a class”, he recalls.

Although his mother raised him as an upright Lutheran, he didn’t take his religious upbringing very seriously. He was close to his evangelical grandparents, but his own father (my grandfather) rarely attended church. It may have been partly due to his lonely time in Madison, partly due to the regular talks with his favorite uncle Art, and partly the result of a young man beginning to take seriously his obligations as an adult, but sometime around then he joined his grandparents and uncle to become a “Born Again Christian”.

He remained an enthusiastic believer for the rest of his life. To this day I have not met a more sincere, devoted Christian than my father. His religious conviction was the absolute center of everything he did, and in all my years of knowing him, I never once saw him waiver. A devoted student of the Bible, he read, memorized, and prayed over the Scriptures every single day.

In his younger days – though this was before I was old enough to pay attention – he might have lived up to the caricature of an in-your-face evangelizer whose enthusiasm goes too far. He genuinely believed the Gospel was the solution to all problems, so naturally he wanted to spread the word. Raised by his mother to be a staid Lutheran, I can imagine he might have over-corrected after converting to become an evangelical early in his 20s.

The man I knew was always polite about his Christianity. Even if at some level he sympathized with those “The End is Nigh” placard-carrying demonstrators you’ll see in urban crowds, he would have thought their approach was counter-productive. My father lived his beliefs, as best he could, through his actions. Living the Christian life wasn’t difficult for him, because at every level, through and through, he believed it.

Patricia Ann Pulokas

My mother shared many of the same experiences growing up in dairy farm Wisconsin, but as the oldest daughter of Lithuanian immigrants, her family values and expectations were even more traditional than the Spragues.

She attended a one-room school house in elementary school, until middle and high school when her parents enrolled her in St. Hedwig’s Catholic School in nearby Thorp, Wisconsin. Her childhood was typical for farm girls of her time: she assisted her mother with household chores, helped with other farm duties like milking the cows or gathering eggs from the henhouse. She was also expected to be responsible for her younger brother, Paul.

She and her best friend left high school hoping to become flight attendants (called “stewardesses” back then). She failed the height test – at 5’8” she was too tall – but a career was the last thing on her mind when her parents enrolled her at the Eau Claire State Teachers College. In theory this would qualify her to become a schoolteacher – a reasonable and respectable job for a woman – but like all of her friends, her real goal was to find a suitable husband (an “M.R.S. degree”, they quipped).

Marriage

And so it was that, just after her 20th birthday, my mother was engaged. Married that July, they set out on a life together that by all accounts was perfectly normal.

And it was. That fall they moved into a small apartment off campus, where Mom took care of the cooking and cleaning while Dad finished his degree. Within a few months she was pregnant with my brother – who was born the following Spring.

By today’s standards, they were married at an eyebrow-raising early age, but it wasn’t unusual at the time. My mother had attended as many of her friend’s weddings before she was married as after. Many of her high school friends were already mothers by the time she had her first baby.

In fact, if anything the norm was to want to be an adult: to own a car, buy a house, have children. The concept of living as an unmarried single during your 20s would have seemed, well, lonely.

And very quickly, by the time my mother was 25 she already had three children. Nobody was lonely in our family.

5.3 Grandparents

I was lucky to know my grandparents and great-grandparents well.

My mother’s parents, the Pulokases, lived a half-hour’s drive north, on a small farm in Reseburg Township near Thorp, Wisconsin. My father’s lived about an hour away, just outside the tiny community of Sheldon, Wisconsin. Both sides of the family were active dairy farmers until I was a teenager, so cows, tractors, and hay fields were a natural part of our lives.

5.3.1 Pulokas Grandparents

The Pulokas relatives of my mother’s side were among the 350,000 immigrants who left Lithuania in the last half of the 19th century. Descended from a man named Matthew Pulokas who arrived in Franklin Vermont in 1900, settling in the Chicago area along with his brother Carl.

Matthew moved to America as the result of what appears to have been an arranged marriage, to Domecella Winskunas a year after his arrival. Like most immigrant farming families, they had many children—ten or more—but only three survived to adulthood, all boys, including my grandfather Anton. The family worked a small diary farm, purchased in 1904, on the south fork of the Eau Claire River in northern Clark County.

The farm was small, and by the time the brothers were in their teens it was no longer necessary to have the entire family work the place, so Anton instead found work as a truck driver, hauling cargo from northern Wisconsin to Chicago every day for a dozen years, until he was able to buy a farm of his own. His property, conveniently located adjacent to the rest of the family, became the home of my grandmother, Martha, the birthplace of my mother and her younger brother, and a wonderful place to play for me and my siblings.

Meanwhile, Carl had a daughter who married a Shainauskas man who died in the 1940s, widowing his Pulokas wife who raised her son Frank in the Chicago area. Frank was much younger than his two older sisters, who both joined a Lithuanian Catholic convent in Chicago. Frank visited the Pulokas farm during his childhood summers and the family remained in contact for the rest of their lives.

My mother’s two uncles, Walter (1902) and Joe (1904) never married but remained at their birthplace, working the farm for their mother while she was alive, and continuing to run the place, hunting and fishing until they themselves were too old to work anymore. Lifelong bachelors, they apparently had no interest in the basics of housecleaning after their mother died. The inside of the house was a mess, with a 1936 calendar posted above the kitchen table, untouched over the years that I visited.

I remember occasional visits to their home as we listened to them talk about the weather. The brothers had uncanny memories about anything weather-related. We could pick a random day anytime in the past half-century and the two would instantly tell us what the weather had been like that day or week.

You could pick any specific date, like “February 2nd, 1944”. Joe would answer “That was cold”. “Ten below”, his brother Walter would add. “A couple days before that big snow storm”, Joe might clarify. They could offer similarly detailed recollections about weather for any week, any decade.

The three brothers left school after the third grade to work full time on the farm, a common – and expected – fate for farm boys of their day. But if their educations were incomplete, it certainly didn’t show in their daily lives.

On our visits to his farm, Grandpa Pulokas would often sit in his rocking chair, head buried in a newspaper. He kept careful records of which cows he raised, how much profit per cow, and many other calculations that today we’d assume require a high school education. I still wonder how, statistically, it can be true that in America so many people graduate without the ability to read and write, when my country grandfather seemed to have no trouble, though he was only in a classroom for a few years.

From Ancestry.com:

When Mathilda Martha G Petruzates was born on April 26, 1905, on the Petruzates farm in Eagle River, Wisconsin. Family legend says that her uncle was charged with the task of registering her name with the town but was drunk and gave the wrong name. For that reason, she always went by her middle name, Martha. Her father, Anton, was 43, and her mother, Anna, was 34. Martha was 35 when she married Anton J Pulokas on May 1, 1940, in Thorp, Wisconsin. They had three children during their marriage. She died on December 17, 1979, in Neillsville, Wisconsin, at the age of 74.

How Martha ended up in Thorp, uprooted from her roots in Eagle River Wisconsin, is a story long lost to history. Well into her late 20s and maybe even past 30, supposedly she had come to the Thorp area to meet my great-uncle, Joe – Anton’s older brother. Nobody knows what happened that might have precipitated the switch.

The Pulokas farm was much smaller than the farms of my father’s side of the family, but to us that made it more personal and friendly. It may have been just that my grandmother Martha was an incredibly sweet and loving woman who greeted us with presents on each visit: her back room was always set up with new toys and was our first destination each time we came over, which was at least once a month.

My mother and grandmother were emotionally close as well, speaking on the phone nearly every day – in spite of the fact that in those days such long-distance calls were charged by the minute. The trip to Grandma’s farm seemed long to us – perhaps the lack of traffic in Neillsville made any trip seem far – through the rolling hills, across the many streams, and past the endless cornfields and pastures of central Wisconsin. Surrounded as we were by so much nature, I guess we didn’t appreciate the countryside as much as I do now and I regret not taking it more seriously and treating it more like the precious experience that it was.

There was never a shortage of things to do at Grandma’s farm. During the summers, with the good weather, we played non-stop outdoors, mostly in the front lawn but sometimes in the cow pastures extending to the woods. The only area we were afraid to venture toward was the back yard, where Grandpa kept a large and scary-looking bull, chained through his nose to a heavy concrete block. We imagined that the bull was dangerous, and we especially avoided venturing near it while wearing red colors, but I never saw it to more than lazily munch the grass and hay that Grandpa had set out for it.

Of course there were plenty of farm chores to do as well, and Grandma let us help: fetching eggs from the chicken coop, pumping water for the bulk tank to cool the milk, harvesting radishes and onions from her vegetable garden.

There were pets too. Grandma kept a house dog, a small mutt she named Buttons. Well-fed from her kitchen scraps, Buttons was the fattest, most obese dog I’ve ever known. He died at some point in my childhood, soon replaced by another half-breed, a chihuahua-like puppy she named “Pepsi”.

Although there were no house cats, like all dairy farms they had plenty of barnyard cats, fed on leftover cow milk and whatever mice or rats that attempted to live on the grain kept over the winter. The cats had many kittens, including one litter of three that Grandma gifted to each of us children. The kittens were to be kept at Grandma’s house, which provided yet another excuse for us to enjoy our visits there. Sadly, like many barnyard cats, these didn’t make it to adulthood, dying one by one of distemper.

Grandma had a green thumb, and her house and yard bulged with pots bearing all manner of flowers and greens. My mother would sometimes consult with her about various planting problems, and somehow anything Grandma touched would end up growing again.

Partly because Grandma was so enthusiastically interested in us, and partly because Grandpa was less loquacious, I didn’t interact much with my grandfather. I suppose he would have been busy with farm chores, less able to spend time with us, and maybe my brother and I would have had more interaction if we had been older and more useful on the farm. Still, I know Grandpa cared about us in his own way.

One birthday he announced that he was taking me to a store to buy me a football. Despite not being much of a sports-minded person, I accepted his gift gratefully, not wanting to explain that I’d probably not get much use out of it.

Death of Grandma Pulokas

In late Fall of my junior year in high school, my grandmother Pulokas came down with what seemed at first to be a sore throat. By the time we saw her at Thanksgiving, it was bad enough that her voice was scratchy, an odd symptom that continued through Christmas until, finally, sometime in the new year she visited a doctor.

I know little about the medical details – my teenage self wasn’t tuned to such things – but eventually we learned that the “sore throat” was a symptom of late-stage lung cancer. Grandma never smoked, lived an exemplary life of rural organic eating with plenty of exercise, so it’s hard to “blame” the cancer on anything in particular except bad luck.

She was in and out of the hospital that year for various tests, and although I’m sure the adults were very concerned, none of the seriousness trickled down to me. She was just Grandma. Always Grandma. Always there.

Something happened that resulted in her admission to the big hospital in Marshfield, and I remember visiting her down the same long corridors that had been familiar to me during my own bouts of illness there: the ever-present statues and crucifixes that adorned St. Joseph’s Catholic hospital, symbols of reassurance to lifelong believers like her.

Somehow I was left alone in the room with her when suddenly she blurted to me: “Well, just know that I’m ready.”

To my evangelical mind trained that salvation only comes through direct faith in Jesus, I found this oddly reassuring and concerning at the same time. I knew on the one hand that she was a serious, practicing Catholic; but on the other hand my evangelical upbringing taught me to be suspicious of hope in heaven based on anything but faith and grace alone. Catholics pray to Mary, not God, and think you get to heaven by listening to the Pope, right? Now I can chuckle at my ignorance, but Grandma’s earnest faith made an impression on me.

5.3.2 Sprague Grandparents

The other side of the family – the Spragues – seemed less approachable, a bit more stand-offish than the loving embraces we received from Grandma Pulokas. Part of the reason may have been geographical: The Pulokas farm was much closer, just over a thirty minute drive. My mother brought us there several times a month, even more when there was no school. But I can’t help thinking that some of the reason we saw the Sprague side as less friendly was that it simply wasn’t possible to be a nicer, kinder, woman than my Grandmother Martha Pulokas.

My grandmother Ruth Sprague was a faithful matriarch who broke every mold of the typical Wisconsin farmer’s wife. Besides the normal work of milking cows each morning, for decades she was a full-time bookkeeper for the local farmer’s co-op, long before it was “normal” for a woman to have a job.

As the only of her siblings to graduate high school, she was proud of her literary tastes. The bookcase in her living room was packed with National Geographic, Readers Digest and various bound books of literature. I remember that she had a copy of The Koran up there someplace, which was exceptionally odd for a farm house back in those days, but that’s the type of person she was. She subscribed to the Wall Street Journal, delivered by mail a couple of days late to their rural farmhouse. The news may not have been fresh, but it revealed her admirable curiosity about the bigger world.

Her husband, my grandfather Donald Eugene Sprague, Sr., had no interest in reading as far as I could tell. Unlike my other grandparents, Grandpa Anton Pulokas, who always seemed to be reading a newspaper when we visited, I’m not even sure I could prove that Grandpa Sprague was literate. Well, that’s not completely true: to run a farm all those years I’m sure he was reasonably good at writing and math, but he showed none of his wife’s interest in life beyond his day-to-day country living.

Their farm was much bigger than the Pulokas farm, with many more cows, and hired hands whose names seemed to change regularly enough that we didn’t bother to get to know many of them. I remember Ted, who Gary and I found to be hilariously funny during our dinners together; and the Menchaka brothers, with their mysterious past – part Indian? Part something? Abandoned by their father?

In a farm community where most families were large, the Spragues were odd in that my father was an only child. Perhaps for that reason, after he left home my grandparents became foster parents, often for kids from troubled homes. I suppose the authorities thought that farm work would teach discipline and skills to struggling boys.

One of these foster kids, a teenaged boy named Robbie, loved to play rough with my brother and me, wrestling us on the ground much more seriously than seemed appropriate. We enjoyed rough-housing as much as any Wisconsin boy, but this kid seemed genuinely interested in hurting us.

We later learned that he had been placed in foster care at a very young age, after accidentally murdering another kid with a baseball bat. Robbie had a thing with baseballs: he broke one of Grandma’s windows with one. She demanded that he pay for the replacement out of his allowance money, but discovering that the cost would be higher than his allowance could pay, she promptly gave him a raise. This was how she thought about life.

Don (Sr) (my grandmother always called him “Don”) developed health problems as he aged into his 50s and 60s, probably due to his life-long cigarette habit. A relatively short man (maybe 5’8” or so), he had a slim build that gradually diverged as his wife became heavier. Sometime in the 1970s, he was diagnosed with kidney disease and had to go on dialysis.

They retired from farming to a life of regular long-distance travel, always by car, and generally to the west and south. My grandfather’s need for regular dialysis made no difference to their plans. Grandma simply looked up dialysis centers along the route, making regular stops as necessary.

Both of my Sprague Grandparents, like my father, had Type O-positive blood.

5.3.3 My Great-Grandparents

My grandparents were the last Sprague holdouts in an area that had once apparently been home to many of their relatives. Howard Sprague (1889-1975), my great-grandfather, had settled there in the 1920s or 30s and raised seven children, all of whom had their own farms at one point or another. After Howard left, the others left too, one by one, moving to cities out west in California or to the south, where they took part in the great American migration away from the farms, building lives in the cities that were much different from the agriculture-oriented world they left behind.

My great-grandfather Howard Sprague and his wife Delia were quite old, well into their 80s, by the time I met them, but they were both spry and full of energy, eager to meet us and spend time together. I feel very lucky that I had those several days to get to know them.

Howard Sprague was a perpetual optimist who enjoyed a life full of regular attempts at reinventing himself. Born in North Dakota, he lived as a farmer for many years while raising his family, ultimately settling in Sheldon, where my grandfather grew up and raised my father. Unlike many of his farmer peers, Howard seemed to do farming out of an interest in business: he saw it as a simple way to earn a living, buy seed for cheap, grow it until harvest and sell at a profit. But there were other ways to earn a living too, including home construction, which he did as a side occupation until, long before I was born, he decided to move near Monterrey California to start a commercial building business. He tried that for a few years, apparently successfully, before moving again, until he ultimately retired to Grand Junction, Colorado, where he lived until his death.

But back in Sheldon, somehow my grandparents held on, lone holdouts against the urbanization that called the rest of the family. As a result they gradually accumulated additional farms, left to them by departing relatives. This, too, made Grandma Sprague’s place seem so much bigger, and a bit more formal, since now the various additional farms were inhabited not by relatives but by renters.

Still, a farm is a farm and there is always plenty to do. Grandma Sprague had planted apple trees in her front yard decades before, and now during the late summer and fall the trees bulged with fruit begging to be picked. She too had a vegetable garden – far larger than the Pulokas one – with rows and rows of pumpkins, squash, sweet corn and much more. Of course, both grandparents’ farms were surrounded by thickets of corn plants, fields that by late summer grew into unnavigable mazes that we kids never grew tired of exploring. The Sprague farm had a separate, large hay barn, full of straw bundles that we turned into non-stop amusement, building our own caves and hideaways, like full-size lego bricks.

And always, the smell of cows, everywhere. “Fresh air”, my mother called it.

5.4 More Relatives

My father was blessed with dozens of cousins thanks to the prolific mating habits of his grandfather and uncles. But we knew few if any of them, and fewer of whatever children were my age. Partly this was a consequence of distance – they were scattered in California, Colorado, Oklahoma – but honestly a bigger reason was a lack of cohesion on that side of the family. “We’re the white sheep of the Sprague family”, we joked.

My great-grandfather, Howard and his wife Delia had seven children: Buren, Don, Art, Lyle, Avanell, Loretta, and Dewey.

Although I probably met each of them at some long-forgotten family gathering, I don’t remember much. Mostly they were just names to me, old people who were somehow connected with the Sprague side.

Art was an exception. He and his wife Doris lived a mile down the road from Grandma’s house – at least when I was very young – a place I remember full of stories of the practical jokes that the couple liked to play on others – and each other.

Their son Kenny, who was several years older than me, might have become a cousin friend but sometime in the early 1970s they moved to Kenosha, in southern Wisconsin, when Doris got a job at a car manufacturing plant.

Other sons of Howard were scattered across the country, and I know little of them except for family stories.

Howard objected when his daughter Loretta wanted to marry her teenage boyfriend, Harold. But somehow they married anyway, a relationship that lasted a lifetime. They lived in Lansing Michigan.

Most of these people carried the Sprague name, and I don’t doubt that if I ever spent time in Eureka California I would bump into descendants, legitimate and otherwise, of Howard’s son Dewey, who married multiple times and had many children and then grandchildren.

Paul and Pat Pulokas

We knew the Pulokas side of the family much better. My mother’s only sibling, Paul, was three years younger than she was, and having moved away from home while he was just beginning high school, she might be expected to not know him very well. But sometime after college, he met and then married Pat Henschel, a part-time registered nurse and family powerhouse.

She met Paul at a bar in November 1966, when she bumped into him on purpose as a way to strike up a conversation. They were college seniors at the time – she in her last year of nursing school, he in his final (fifth) year in agricultural engineering. They dated a lot after that, and by graduation in the summer of 1968, they were essentially engaged. He started a new job at International Harvester, but within six months he received his draft notice and soon was headed to Fort Dietrich Maryland for the next two years.

They corresponded by mail nearly every day and the following year he got her a ring and brought her to the farm to meet his parents. Her mother was strongly opposed to her marrying a Catholic, so it took another many months to work that out. Finally in 1969, she moved to Maryland, got a job at a hospital and an apartment there so they could see each other every weekend. They married in 1969.

It never seemed odd to us that Paul wasn’t much of a talker. Like his father (my grandfather), he was married to somebody who was far more conversational, so perhaps these Pulokas men simply never bothered to speak much to us. What would be the point, since their wives knew everything and kept everyone in touch anyway?

My earliest memory of Paul is from a hotel room near Madison Wisconsin, where we stayed while attending his wedding. I vaguely remember a long reception, with loud music and dancing that I thought overly boring. A much more exciting event at the time was the cartoon “Underdog” playing on our hotel room TV set. I also vaguely remember my brother being ill, perhaps from the abundant food.

Sometime a few years later, we visited Pat and Paul at their home in Bloomington Illinois to meet their first child, Tony Pulokas, my first cousin. It was a six hour drive that we could afford to undertake only on special occasions, like summer vacations. For Christmas or Thanksgiving, they would drive up north to meet us.

More children, and more cousins, arrived throughout the 1970s, eventually giving me four first cousins: Tony, Mark, Jim, and finally Katie (born in 1980). Because of the distance, we saw them at most once or twice a year. The boys were several years younger than we were – a difference that matters more at that age – so although I have pleasant memories of our yearly visits, we didn’t know each other as well as many families.

Uncle Raymond

Raymond was born to Herman and Mary Faerber in McKinley Wisconsin. He was baptized into the Christian faith on January 7, 1921 by the Rev. A. F. Hemer at Jump River, Wisconsin. His sponsors were Ella Beutler, Reinhold Luedke and Frank Beutler. On July 2, 1933, he was confirmed into the Christian faith at Trinity Lutheran Church, Sheldon Wisconsin by the Rev. O.H. Marten.

On October 27, 1942, Raymond entered into active military service with the United States Army. He took part in battle and campaigns in the vicinity of Rome – arno, the Northern Appennines and Po Valley. He was awarded the Good Conduct Medal, the American Theater Service Medal, the European-African-Middle Easter Theater Service Medal and Two Overseas Service Bars. His rank was Private First Class.

Raymond passed away at Rusk County Memorial Nursing Home on Monday January 27, 1998 at the age of 79 years, 11 months and 1 day.

He was preceded in death by one brother, Reuben.

February 25, 1918 - January 26, 1998

Buried in Mt. Nebo Cemetery in Jump River, Wisconsin

My grandmother’s brother, Raymond, fought in Italy during World War II, and that seemed to be his favorite topic conversation ever since. Not the war, per se, but his observations about sinfulness and how small temptations could grow into bigger ones.

His sister, my grandmother Ruth, was only daughter in a family rocked by devastating tragedy. Their father (my great-grandfather Herman Faerber) had lost his left arm in an accident (sawing wood?) early in his life — I’m not clear whether it happened before or after his marriage.

Maybe it’s understandable that everyone in that family spent time in mental institutions (including my grandmother, of which I’ll discuss later). The eldest brother, Buren, had already been long institutionalized by the time my parents married, apparently coming to believe that he was God himself — on the only time he was introduced to my mother, he refused to shake with his right hand because “I’m holding the world in it”.

Their mother, Marie, died when Ruth was only 18 years old, of breast cancer, after what was no doubt a long bout of unspeakable pain and suffering. The mother and daughter were apparently quite close, so I’m sure it made a devastating impression on my grandmother, though it never occurred to us to ask the details.

Marie was, we were told, from a “rich” family in North Dakota and looked down on her husband Herman, who dragged her away from her happy family to live in an unsettled part of northern Wisconsin, near the Jump River, where somehow they had secured some land for farming. The family arrived in an ox cart (or so I’m told), amid forests so thick they had to secure permission from the county to graze their cow in a public park while they cleared their own property.

They spent their first Wisconsin winter on a dirt floor in a shelter barely worthy to be called a shack. The “real” house they built in the Spring became Raymond home for the rest of his life, except that brief period during the war. The property was situated near a river, but for daily use they dug an artisan well in the winter: one foot per day until they struck water at something like 30 feet.

I knew Raymond as a regular guest at Thanksgivings and Christmases, when you could reliably assume he would repeat his many stories of military service in Italy. As with many WW2 veterans in my experience, if he had seen action he didn’t discuss it. Rather, he regaled us with anecdotes of the depravity of his fellow soldiers, some of whom — the horror! — played blackjack.

Still, he was always friendly enough that it was easy to forgive his orneriness as a symptom of being a lifelong bachelor. Grandma would later chide him for “not marrying that Mennonite girl” when he had the chance, a woman who, I heard, remained unmarried herself.

My new wife and I visited Raymond in the mid-1990s, not too long before he passed away. His house was spartan, though I remember it being much cleaner than the bachelor home of my other great-uncles — the Pulokas brothers Joe and Walter, who had never learned to clean up after their mother died. Raymond kept himself busy growing a large garden, and tending to his main prize: an elaborate grove of maple syrup trees, carefully rigged with tap lines that carried the sap automatically to an endpoint where he would boil it into dozens, maybe hundreds of jars of maple syrup each spring.

Although — perhaps because — he lived alone for so long, Raymond was a fiercely religious Lutheran who read the Bible regularly. Few things brought out a livelier side of him than a discussion about non-King James Version translations. I remember a lengthy lecture once about how the modern translators have deliberately inserted some heresy into various verses, the details of which I no longer recall, but which to him seemed of urgent importance.

He wrote notes on what he read, written in the smallest possible handwriting, edge to edge on whatever scraps of paper he could procure. After his death, the family found hundreds and hundreds of these scrupulously-written page of commentary scattered throughout the house.

Raymond and my grandmother had an older brother, Buren, who I never met. Well that’s not quite true. I was a few weeks old when, in April 1963, my mother carried me to the funeral of their remaining parent, Herman Faerber, my great-grandfather. When my mother met Buren there, he apologized that he could not shake her hand. “I’m God”, he explained, “and I need to hold the world in that hand”.

I know very little else about Buren. I dimly remember sitting in a car outside a mental institution in Owen Wisconsin, waiting on my father who had stopped in to visit. Buren was apparently quite intelligent, able to recall details of a newspaper after a brief skim. It was never explained to us how he was institutionalized. It’s one of those family mysteries that was probably so traumatic that at the time nobody wanted to discuss it further. Eventually, enough years passed that it became permissible to talk, gently, about the details, but by then, most of those who knew the facts were gone.